Ek Stasis

October 2009

The underlying impulse that fuels these paintings has echoes in the origins of art: the primal urge to see evidence of hand on surface, but the thoughts and feelings that give this impulse tangible form for Jeannette Siebols arise from Greek Mythology. The title of the exhibition describes her heightened emotional response to these myths.

While being drawn to the visual poetry of this series, I did wonder why the texts are not legible. But the thought occurred to me that the very marks that prove identity, written signatures, are often indecipherable.

And then I realized another thing: the literal meaning of the text has already served its purpose – to prompt not only emotion in the painter, but also choreography of the brush. After all, in this series the freedom to improvise is paramount: the meaning behind the text may be the subject-matter but the paint itself is the object-matter.

The obscurity of the text, clouded by layers of paint, allows room for interpretation, so the spaces can evoke both landscape and soundscape.

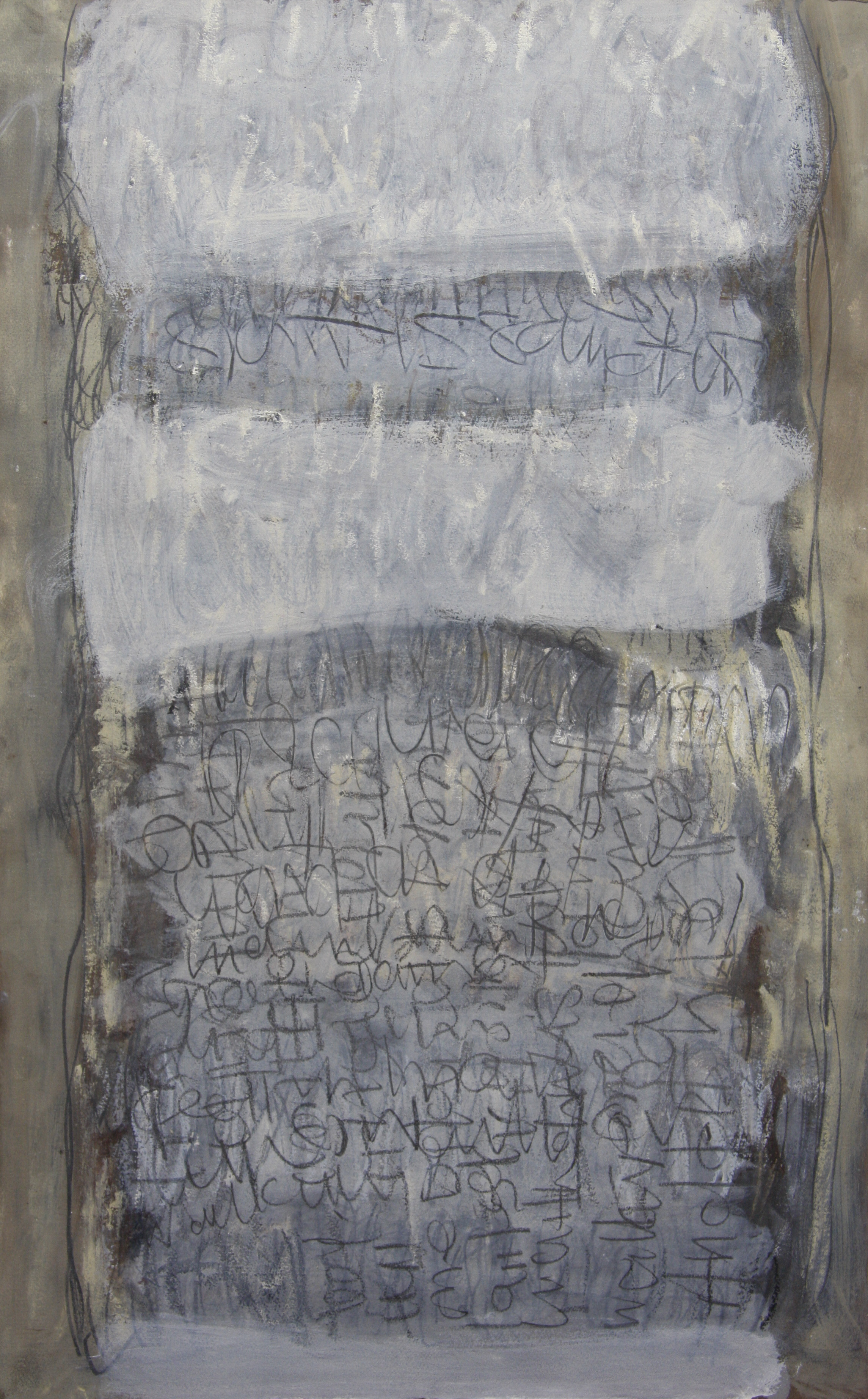

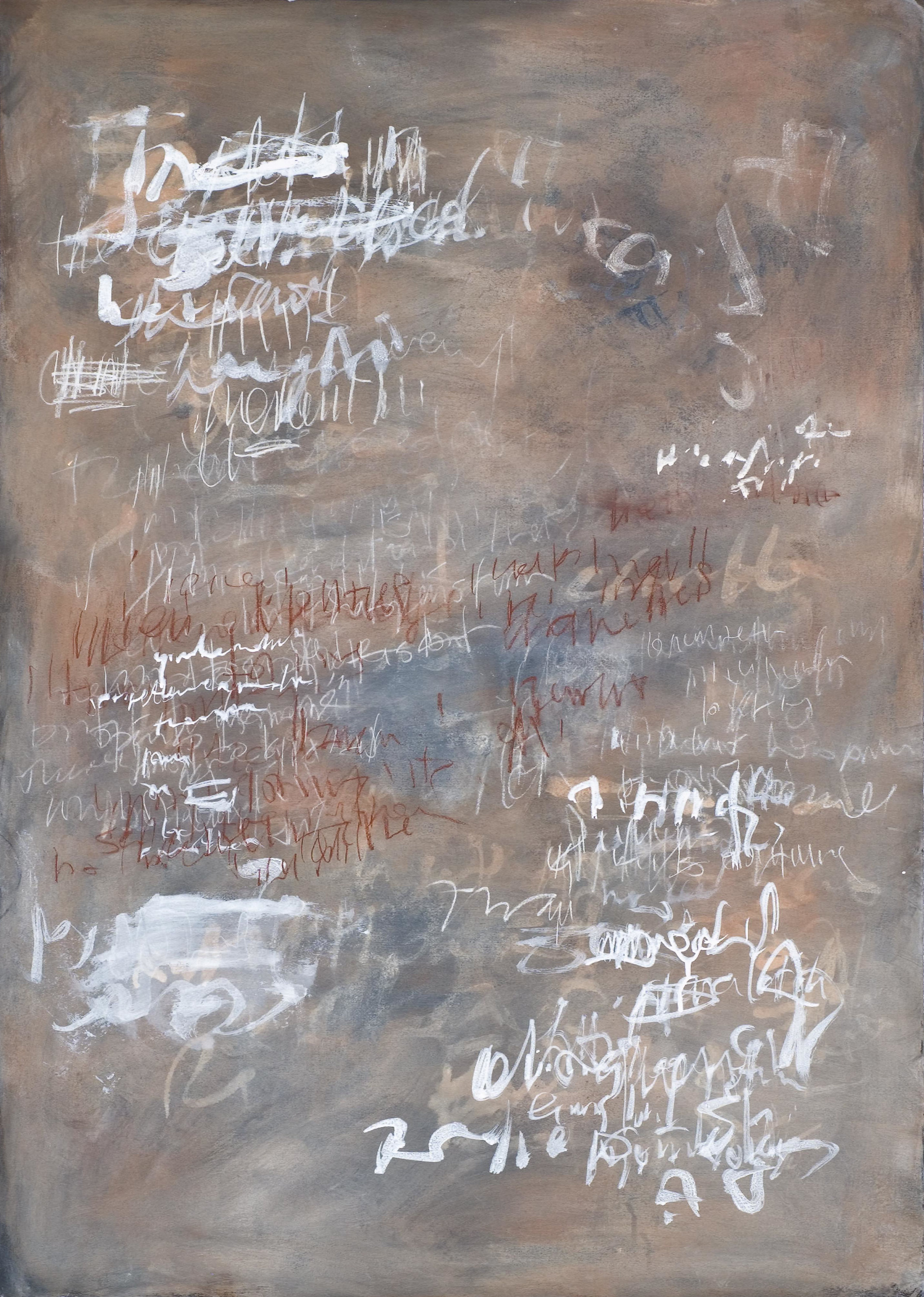

When conjured as landscapes the texts are often woven into a middle ground with the broader, veiling brushwork alternating between background and foreground.

While imagining these works as soundscapes I am reminded that, looking at text I hear phonetics in my mind’s eye. Even when the language is unfamiliar I am curious about the sounds associated with the symbols.

In these paintings I hear fragments of song almost lost in movement of air and barely audible love whispers.

John Peart, 2009

Siebols' Palimpsests: Painting the Violence of History

This essay is a meditation on the figuration of history and writing in Jeannette Siebols’ calligraphic paintings. The governing metaphor in this series of paintings is the palimpsest. Each canvas represents a multi-dimensional layering of script. The figure of the palimpsest introduces an explicitly historical dimension in a series of paintings that challenges the traditional ahistoricism of abstraction even as it draws upon many of its elements. The scriptural economy of Siebols’ canvases is inscribed on iconic blocks of colour which reference both the Rosetta Stone and the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments. These two iconic figures establish the ground upon which is dramatised the historical durability and persistence of the word/logos, as the rule of law.

Inscribed on this foundational ground, however, is a complex network of signifiers and relations of force. The calligraphic signs which traverse this ground simultaneously throw into question the very concepts of durability and persistence. I specifically use the term “traverse” in order to draw attention to the kinetic and thus dynamic quality of Siebols’ calligraphic markings. Her writing, painterly and evanescent, draws attention to kinetic acts of graphic inscription and corporeal gesture. Her calligraphic strokes are inscribed with a sense of energy and urgency which underscores questions of temporality and human mortality in the face of the transhistorical nature of the logos.

In the context of the palimpsest, the sedimentation of scripts which constitutes the textual fabric of Siebols’ canvases points to the violence of history. Siebols’ paintings place under interrogation questions of origin and foundation. Precisely by inscribing on the foundational ground of tablets and stones a series of palimpsests, she invokes a Nietzschean understanding of history as genealogical. Friedrich Nietzsche’s genealogical conceptualisation of history posits an interminable series of originary moments which are repeatedly displaced, rewritten or effaced with each new instance of domination and becoming master (1968: §514). In a similar vein, Thomas Carlyle describes the dynamic process by which history is continuously reinterpreted and thereby re-written: “[History], at each new lengthening, at each new epoch, change[s] its proportions, its hue and structure to the very origin” (1969: 111). In this passage, Carlyle points to the very historicity of history; and by this I mean the manner in which history can only ever signify in terms of epistemological category and not as an ontological datum. History, in this view, and as graphically represented by Siebols’ paintings, emerges as almost indecipherable polyglossic text inscribed with myriad voices, stratified by countless movements of conquest and contestation. This polyglossic view of history is brilliantly described by Carlyle in his essay “On History”:

… that complex Manuscript, covered over with formless,

inextricably-entangled unknown characters, … nay,

which is a Palimpsest, and had once a prophetic

writing, still dimly legible there, … some letters, some

words, may be deciphered; and if no complete

Philosophy, here and there an unintelligible

precept, available in practice, may be gathered: well

understanding, in the meanwhile, that it is only a little

portion we have deciphered; that much still remains to

be interpreted; that History is a real Prophetic

Manuscript, that can be fully interpreted by no man [sic].

(1969: 61)

Siebols’ painterly writing, inscribed on the ground of such prophetic manuscripts as the Ten Commandments, functions to interrogate the discipline of hermeneutics. The practices of archaeology and historical recovery are problematised by the graphic fact that her scriptural signs and calligraphic markings are in various states of decomposition and metamorphosis: a letter or word here is already metamorphosing into a pure graphic gesture which undoes its semantic or lexical status. A word or phrase bleeds into its ground and vice versa, blurring that axis of difference which establishes the conditions of possibility for meaning. A word of phrase becomes unintelligible or unreadable at the site where the parchment has decayed or the stone tablet has been attacked and mutilated. These lacunae defy the desire for the total recovery of meaning as they contest the possibility of a pure presence not already indebted to a determining absence; effectively, Siebols’ use of such lacunae contests what Derrida terms the ‘hermeneutic hold,’ with its inexorable desire to make meaning even in the face of nonsense (1979: 99).

The kinetic quality of Siebols’ calligraphy materialises invisible signs of force and violence. Her writings engrave “tracks” across the tablets and manuscripts of history. The “track,” as a Derridean metaphor for writing (1976: 106-108), encodes the physical violence of carving and inscribing a surface or terrain with the logos: the imprimatur of the word and its dominant meaning thereby signifies possession and mastery. In the context of Siebols’ canvases, we can appreciate Derrida’s profound Nietzschean meditation on the writing of history and the will to power: “This infinite passage through violence is what is called history” (1976: 106-107).

Siebols’ paintings graphically represent the violence of history. Inscribed of the symbolic ground of stones, tablets and stained and ancient parchments is a display of historical inaugurations and rechristenings as signified by the broken and reconstituted fragments of text. Viewed as so many palimpsests, her paintings simultaneously expose and obscure the heterogeneous strata of history. The layers of paint, the erasures and superimpositions constitute the physical and symbolic fabric of her canvases. Siebols’ use of such foundational or “Ur” texts as the Rosetta stone (which, through its use of three parallel languages and writings, supplied the key to the decipherment of multiple ancient cultures) and the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments (as the sacred foundation of western law and morality) and her simultaneous defacement and overlaying of such iconic ground by a Babel of signs, gestures and voices – all this marks her work with distinctly Nietzschean inflections:

Have you every asked yourselves sufficiently how much

the erection of every ideal on earth has cost?

How much reality has to be misunderstood and slandered,

how many lies have had to be sanctified,

how many consciences disturbed,

how much “God” sacrificed every time.

If a temple is to be erected a temple must be

destroyed: that is the law (1969: § II, 24).

On the symbolic ground of arche texts such as the Bible and the Rosetta Stone, Siebols stages a collision of signs and the stratification of scripts; her painterly surfaces, with their layerings of colour and signs, bear witness to the flux of emergent and residual cultures; she choreographs a polyglossia of voices and an admixture of signifiers that often occupy liminal positions between word and ideogram, between lexis and pictura, between graphic gesture and calligraphic sign. Her canvases stand as testaments or testamurs to the violence of history and the repeated sacrifice of so many gods. In the context of Siebols’ paintings, the Nietzschean question as to how much God has been sacrificed in unquantifiable. The measures that are made available to us by Siebols’ dense yet evanescent palimpsests are fragmented – so many shards and sedimentations which provoke meaning even as they withdraw or efface the very possibility of signification. And it is here, possibly, in this double gesture which occupies an utopic space between one and the other, that the trace of God signifies.

Joseph Pugliese

Professor Joseph Pugliese is Research Director of the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

References

Derrida, Jacques (1976) Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Derrida, Jacques (1979) Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles/Eperons: Les Styles de Nietzsche, trans. Barbara Harlow, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carlyle, Thomas (1969) A Carlyle Reader: Selections from the Writings of Thomas Carlyle, ed. G. B. Tennyson, New York: Modern Library.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (1969) On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufman, New York: Vintage Books.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (1968) The Will to Power, trans. Walter Kaufmann, New York: Vintage Books.